END|Strength Part 1: The Basics and Who the Hell Is Doing This Stuff

END-Strength – Part 1: The Basics and Who the Hell Is Doing This Stuff?

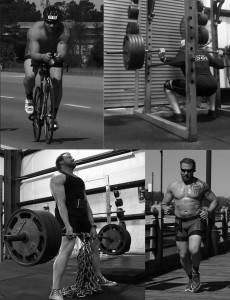

For decades conventional “wisdom” has been endurance work not only inhibits, but destroys strength and strips off hard earned muscle. So what if I told you that a guy did a half iron distance triathlon (1.2 mile swim, 56 mile cycle, 13.1 mile run) in 6 hours and the following day hit a 505lbs squat and 565lbs deadlift?  Would that change your mind… or at least get your attention?

For decades conventional “wisdom” has been endurance work not only inhibits, but destroys strength and strips off hard earned muscle. So what if I told you that a guy did a half iron distance triathlon (1.2 mile swim, 56 mile cycle, 13.1 mile run) in 6 hours and the following day hit a 505lbs squat and 565lbs deadlift?  Would that change your mind… or at least get your attention?

Humans can, in fact, develop both exceptional strength and endurance simultaneously. In this, part 1, I will explain the basics of END-Strength and who is doing this stuff. In the subsequent parts of this series, I’ll talk specifically about programming methods and then running, cycling and swimming.

Before we advance any further, let me be absolutely clear: by no means am I claiming a human can be as strong as the strongest powerlifter or as fast as the fastest marathoner while training for and developing strength and endurance simultaneously. The training an individual must undergo for strength and for endurance compete for recovery. They do not compete for adaptations, but they certainly do not support each other. Realizing this allows us to not only recognize the compromise but actually relish it. The athletes I train are now enjoying the development of the abilities to both move really heavy things and to also move themselves quickly over long distances. The advent of tests like the 666 (600 Squat, 600 DL, sub 6 minute mile run) and its kin, the 555 and 777, are examples of this new endeavor gaining some real traction in the fitness world.

While those challenges are fun and sound difficult, they are short and do not really possess a component of endurance. A mile is a sprint and if managed properly, the training for it can improve strength.The athletes to which I am referring to are doing long distance work, IronMan triathlons, marathons, 50ks, hikes, and missions in the mountains of Afghanistan while also hitting some impressive numbers in the gym. I tend to define an event as endurance at 90 minutes or longer. There are plenty of races of shorter duration, but physiologically, endurance begins at or around 90 minutes.

The principles of an END-Strength Program, like all effective training, include specificity, progressio n, overload, adaptation and recovery. So it is not the principles, but the approach and application of the principles that set this training apart. By attempting to develop such opposing physiological adaptations, it very easy to increase the allostatic load beyond what the body is capable of recovering from in a very short time. Training takes a back seat to recovery.  Ambition has to be carefully balanced with patience.

n, overload, adaptation and recovery. So it is not the principles, but the approach and application of the principles that set this training apart. By attempting to develop such opposing physiological adaptations, it very easy to increase the allostatic load beyond what the body is capable of recovering from in a very short time. Training takes a back seat to recovery.  Ambition has to be carefully balanced with patience.

There are basically three types of athletes who will find this helpful, each with their own unique challenges.

- strength athletes interested in improving endurance

- endurance athletes who would like to add strength and/or size

- the athlete who has not attained a high level of either and desires to develop both

I have encountered and worked with more strength athletes who wanted to improve their endurance. The reasons have varied from weight loss and improving overall health, a desire to compete in endurance events, and military personnel who need conditioning for an upcoming deployment or selection course. Of the three aforementioned types of END-Strength athletes, the athlete who already possesses a highly developed level of strength is possibly the most difficult of the three to train. This is largely due to the simple fact endurance work is painful and, by definition, constant for periods of relatively long times. Endurance training is in stark contrast to everything the strength athlete is comfortable with. Yet while the two types of training are polar opposites in terms of physiological stimuli, it seems the issues and inhibitions are more psychological, than physiological. The pains associated with endurance work, accompanied by what is often interpreted as slow progress, can be mentally defeating to an athlete. It is important for the athlete to know that just as it can take a year to increase a max lift by only 20lbs, it can take just as much time to drop a minute off a 5k run time. And just like lifting, the rate of adaptation to endurance training slows after the initial period of exposure.

Endurance athletes adding strength training to their work are slightly easier to train. Their reasons for adding weights in addition to their  endurance training range from trying to increase wattage production, or power, to their endurance work. Others come from endurance to strength seeking rehab for an injury. This one is interesting, since there is little rehab that strength work actually does for common injuries associated with endurance sports. The rehab an endurance athlete experiences while taking time off from endurance training, is more likely the time off from endurance work than the strength work itself… but that is another article entirely. In recent years I have seen an uptick in endurance athletes who simply say they are bored. Let’s face it, doing the same thing for hours on end can become boring. Of course, quite a few say they just want to be stronger. It is no secret the purely endurance trained athletes are considered weak in today’s fitness world. Worth noting here is, the one reason I have never encountered for an endurance athlete adding strength work is they read one of those ridiculous articles in T-Nation, or other strength biased sites, by some strength guy who has never even ran a 5k about the completely unfounded benefits of strength training for endurance athletes. Fact: strength training helps running the same as Yoga will increase your 1 rep max Squat. No matter their reason, endurance athletes seem to respond faster to strength work, at least initially, than in comparison to strength athletes who take up endurance. That is until we try to get them to produce their true potential intensity. That can be difficult, as it can take years of training to get highly conditioned endurance athletes to elicit the adaptations needed to produce real 1 rep max efforts. This scenario is manifested by the ability of an athlete to hit sets of 6, 8 or more reps with 90% of their 1 rep max.

endurance training range from trying to increase wattage production, or power, to their endurance work. Others come from endurance to strength seeking rehab for an injury. This one is interesting, since there is little rehab that strength work actually does for common injuries associated with endurance sports. The rehab an endurance athlete experiences while taking time off from endurance training, is more likely the time off from endurance work than the strength work itself… but that is another article entirely. In recent years I have seen an uptick in endurance athletes who simply say they are bored. Let’s face it, doing the same thing for hours on end can become boring. Of course, quite a few say they just want to be stronger. It is no secret the purely endurance trained athletes are considered weak in today’s fitness world. Worth noting here is, the one reason I have never encountered for an endurance athlete adding strength work is they read one of those ridiculous articles in T-Nation, or other strength biased sites, by some strength guy who has never even ran a 5k about the completely unfounded benefits of strength training for endurance athletes. Fact: strength training helps running the same as Yoga will increase your 1 rep max Squat. No matter their reason, endurance athletes seem to respond faster to strength work, at least initially, than in comparison to strength athletes who take up endurance. That is until we try to get them to produce their true potential intensity. That can be difficult, as it can take years of training to get highly conditioned endurance athletes to elicit the adaptations needed to produce real 1 rep max efforts. This scenario is manifested by the ability of an athlete to hit sets of 6, 8 or more reps with 90% of their 1 rep max.

The third group, those who want to develop both, are typically the easiest type to work with .This is more because of where they come from, than either physiological or psychological reasons. These guys and gals are typically CrossFit athletes or military personnel. CrossFitters tend to have decent strength, a little endurance, undeniable work ethic, and of course, their signature, often annoying level of motivation and enthusiasm. The hardest part of training a CrossFitter to develop anything, even CrossFit, is to get them to take recovery days and not train at a million percent intensity in every workout until they crash. Their “messing in the middle” makes them ready to train for strength and endurance. They respond very well I attribute that to going to 3 or 4 training days per week on an END-Strength program, from the typical 10 training days per week so many CrossFitters follow. Military guys just do what you tell them to and take pride in it. The biggest thing to worry about with them is many of those guys and gals will push through a small injury, ultimately turning something small and manageable into something that requires serious medical attention.

.This is more because of where they come from, than either physiological or psychological reasons. These guys and gals are typically CrossFit athletes or military personnel. CrossFitters tend to have decent strength, a little endurance, undeniable work ethic, and of course, their signature, often annoying level of motivation and enthusiasm. The hardest part of training a CrossFitter to develop anything, even CrossFit, is to get them to take recovery days and not train at a million percent intensity in every workout until they crash. Their “messing in the middle” makes them ready to train for strength and endurance. They respond very well I attribute that to going to 3 or 4 training days per week on an END-Strength program, from the typical 10 training days per week so many CrossFitters follow. Military guys just do what you tell them to and take pride in it. The biggest thing to worry about with them is many of those guys and gals will push through a small injury, ultimately turning something small and manageable into something that requires serious medical attention.

The big thing I try to leave athletes with about this type of training, while different groups of people have been doing it for a long time, the push toward maximizing both is new. Therefore the methods we are using to develop this discipline are evolving. It is challenging and fun, so more and more athletes are trying it. A few years ago I would have laughed if someone said a there was athlete who totaled elite and raced an IronMan in less than 11 hours. But now, I am fairly certain it will happen in the next two, maybe three years.